This column brings together 45 Vox columns on the economics of climate change with the aim of (1) providing an overview of some of the key issues from the economist’s perspective, (2) stimulating further research, and (3) demonstrating how CEPR is fully engaged with this central debate of our times

Submerged beneath the flood of information, initiatives,

ideas, and pronouncements, it is hard to keep sight of what is needed

for the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Submerged beneath the flood of information, initiatives,

ideas, and pronouncements, it is hard to keep sight of what is needed

for the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. This column

introduces a new eBook that brings together 45 Vox columns on the

economics of climate change with the aim of (1) providing an overview of

some of the key issues from the economist’s perspective, (2)

stimulating further research, and (3) demonstrating how CEPR is fully

engaged with this central debate of our times and how the power of its

network can promote excellent research and relevant policy.

-

-

Laurence Kotlikoff, Felix Kubler, Andrey Polbin, Simon Scheidegger

-

Francesco Caselli, Alexander Ludwig, Rick van der Ploeg

-

Davide Furceri, Michael Ganslmeier, Jonathan D. Ostry

-

Surely

there can be hardly anyone left who truly doubts that climate change is

real and that it is here. The recent experiences of severe weather

events – floods, fires, droughts, and storms – visibly drive home what

scientists have been saying for years: global warming threatens life on

a planetary scale; it is man-made, predictable and, although not

reversible, its further escalation is mitigable.

Today, it is rare to

have conversations of the ‘but there was always climate change, and who

says that this time is different’ type. Instead, both public and

private actors seem to be aggressively embracing the fight against

climate change. Rare indeed, these days, is the financial institution

that does not promote its environmental, social, and governance (ESG)

credentials. At the time of writing, world leaders are meeting for the

COP26 Conference in Glasgow and expectations are simultaneously high and

low. There are high expectations for some further progress but low

expectations of sufficient progress towards the goal of limiting global

warming to 1.5°C.

Submerged beneath

the flood of information, initiatives, ideas, and pronouncements, it is

hard to keep sight of what is needed for this goal. It is easy to get

lost, primarily because the science of climate change is complicated,

requires very long-run forecasts, and involves large confidence

intervals. The same is true of the economics of climate change: separating the signal from the noise, filtering out the quality research is hard.

Research published by CEPR and VoxEU has served this purpose for years: it filters and disseminates the economic research you ought to read.

A new CEPR eBook

brings together 45 Vox columns on the economics of climate change,

mostly published over the past 2–3 years (Weder di Mauro 2021). The

sheer quantity is testimony to the acceleration of research, knowledge,

and interest in the economics profession. I had to limit the number of

columns chosen and to exclude many interesting pieces from this

collection. The cut-off date was beginning of October 2021 and my

selection bias was for recent and solutions-oriented

contributions. However, in a few cases I have included older pieces,

those that trace some of the ‘history of thought’. Below, I highlight a

few selected insights on the economics of climate change as illustrated

in this collection, but first I want to focus on the science of climate

change.

Download Combatting Climate Change: A CEPR Collection here.

Science first: Some numbers worth remembering

To keep eyes on the goal, a few numbers from the latest report of the IPCC are extremely helpful.1 The numbers are: 40, 300 and 2,390. Forty gigatonnes represents the current yearly emissions of CO2

at the global level, 300 gigatonnes is the remaining carbon budget of

global emissions, if the 1.5°C is to be reached with high (more than

80%) likelihood, and 2,390 gigatonnes of CO2 is the estimate of cumulative historical emissions since 1850 already in the atmosphere.2 These are sobering numbers for several reasons.

First, the 2,390

gigatonnes shows the size of the historical burden. Past emissions mean

that the world has already almost exhausted the total carbon budget to

limit global warming to 1.5°C. These emissions will remain in the

atmosphere for hundreds of years to come and have already warmed the

earth by about 1°C (over preindustrial levels). It is noteworthy that

this historical burden was accumulated almost exclusively by high-income

countries.

Second, the 300

gigatonnes remaining budget is sobering because it is absolute. This is

all that remains, full stop. This is how much this and any future

generations have left if warming is to be limited to no more than

1.5°C. At the current rate of 40 gigatonnes per year, the world has

about eight years left. To my mind, this simple fact is such a powerful

illustration of the challenge: the famous race to net zero needs a fast

start if we are to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

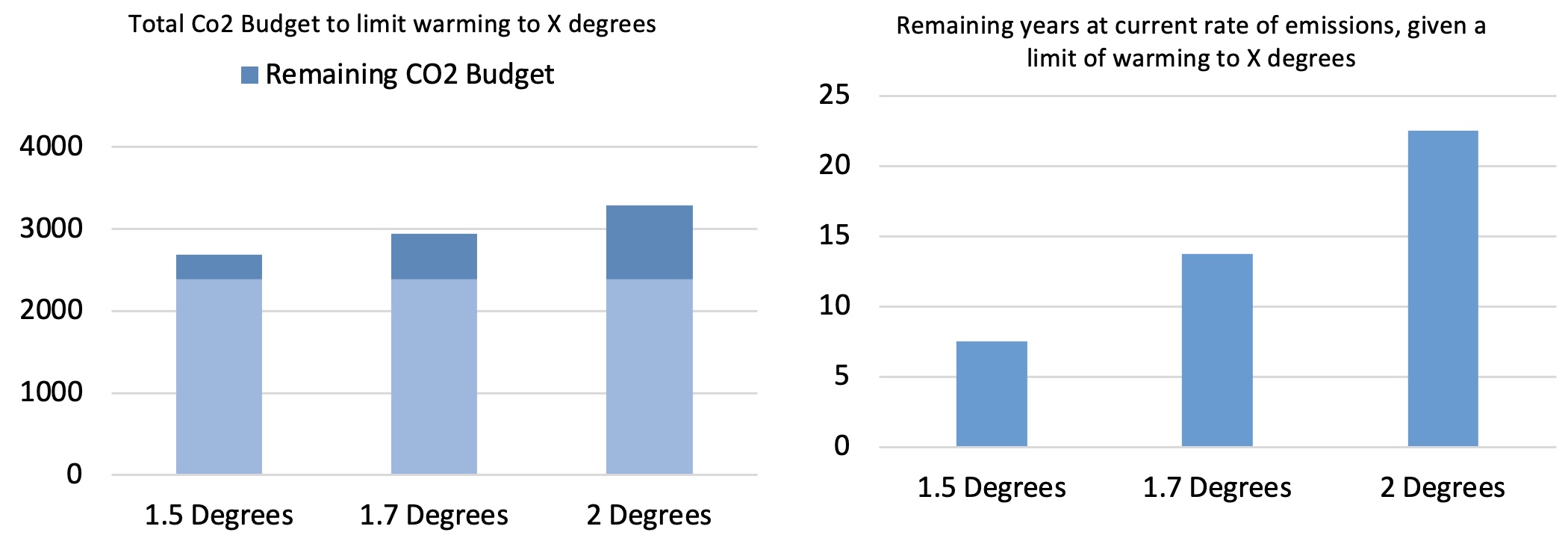

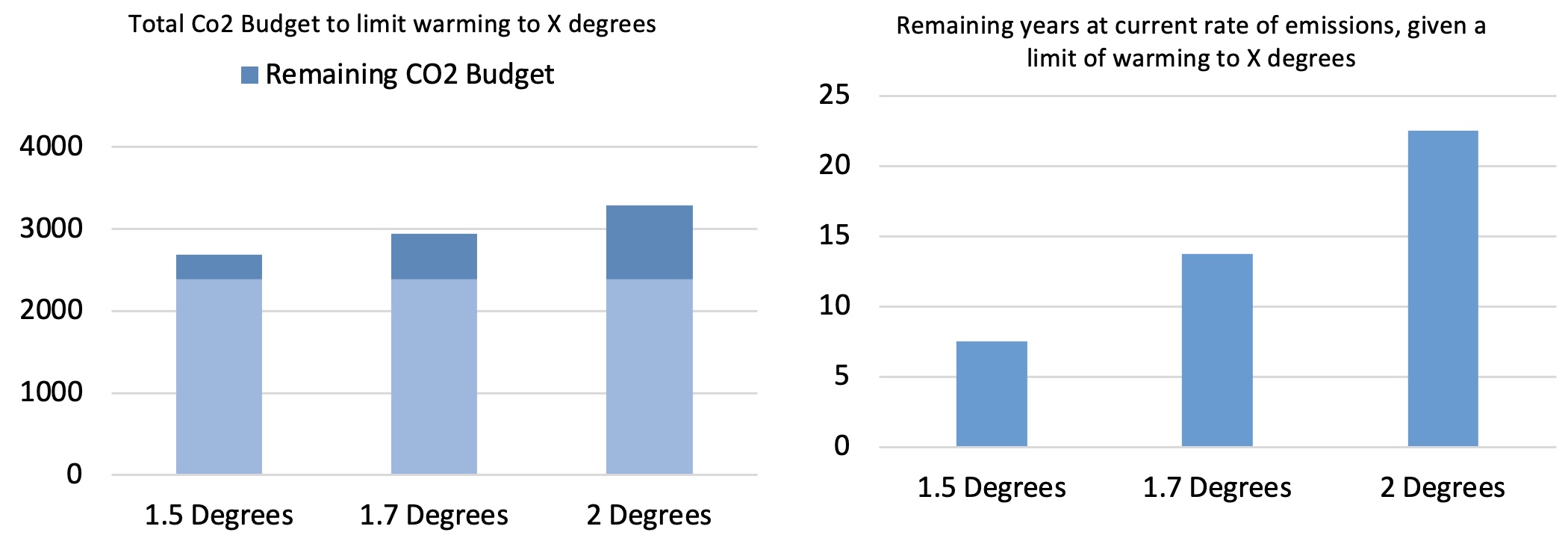

Were the world to

give up on the 1.5°C target and set the limit to 1.7°C or 2°C, the

remaining carbon budgets would amount to 550 and 900 gigatonnes,

respectively. This would allow a bit more time to get to net zero, as

illustrated in Figure 1, but it does little to reduce the urgency to act

and the environmental costs of any further delays.

Figure 1

Source: Author[s] calculations based on Table SPM.2 . IPCC Climate Change 21, The Physical Science Base,

If we were to

translate the remaining budgets into minutes until midnight, the clock

would say that it is 7 minutes to midnight for 1.5°C, 11 minutes to

midnight for 1.7°C, and 16 minutes to a midnight of 2°C warming. It is

worth noting that although the relationship between emissions and

warming seems to be near linear, the consequences of higher temperatures

are not. Another way of looking at these numbers is to conclude that we

need to develop carbon extraction technologies very fast and at

scale. Unfortunately, this technology does not seem to be ‘just around

the corner’.

Is the economics profession rising to the challenge?

Given the size of

the challenge, what are economists doing? Not much, according to Andrew

Oswald and Nicolas Stern (Chapter 1). They look at the number of papers

on climate change published in top economics journals and conclude that

the economics profession has been failing the world. According to

their count, the Quarterly Journal of Economics (QJE), for

instance, had not published even one article on the economics of climate

change until 2019 (a quick Google search for climate and QJE suggests

that this may be unchanged, although it does reveal one QJE article

published in 1917 on climate change as an element in the fall of Rome).

Surely

there can be hardly anyone left who truly doubts that climate change is

real and that it is here. The recent experiences of severe weather

events – floods, fires, droughts, and storms – visibly drive home what

scientists have been saying for years: global warming threatens life on

a planetary scale; it is man-made, predictable and, although not

reversible, its further escalation is mitigable.

Today, it is rare to

have conversations of the ‘but there was always climate change, and who

says that this time is different’ type. Instead, both public and

private actors seem to be aggressively embracing the fight against

climate change. Rare indeed, these days, is the financial institution

that does not promote its environmental, social, and governance (ESG)

credentials. At the time of writing, world leaders are meeting for the

COP26 Conference in Glasgow and expectations are simultaneously high and

low. There are high expectations for some further progress but low

expectations of sufficient progress towards the goal of limiting global

warming to 1.5°C.

Submerged beneath

the flood of information, initiatives, ideas, and pronouncements, it is

hard to keep sight of what is needed for this goal. It is easy to get

lost, primarily because the science of climate change is complicated,

requires very long-run forecasts, and involves large confidence

intervals. The same is true of the economics of climate change: separating the signal from the noise, filtering out the quality research is hard.

Download Combatting Climate Change: A CEPR Collection here.

Science first: Some numbers worth remembering

To keep eyes on the goal, a few numbers from the latest report of the IPCC are extremely helpful.1 The numbers are: 40, 300 and 2,390. Forty gigatonnes represents the current yearly emissions of CO2

at the global level, 300 gigatonnes is the remaining carbon budget of

global emissions, if the 1.5°C is to be reached with high (more than

80%) likelihood, and 2,390 gigatonnes of CO2 is the estimate of cumulative historical emissions since 1850 already in the atmosphere.2 These are sobering numbers for several reasons.

First, the 2,390

gigatonnes shows the size of the historical burden. Past emissions mean

that the world has already almost exhausted the total carbon budget to

limit global warming to 1.5°C. These emissions will remain in the

atmosphere for hundreds of years to come and have already warmed the

earth by about 1°C (over preindustrial levels). It is noteworthy that

this historical burden was accumulated almost exclusively by high-income

countries.

Second, the 300

gigatonnes remaining budget is sobering because it is absolute. This is

all that remains, full stop. This is how much this and any future

generations have left if warming is to be limited to no more than

1.5°C. At the current rate of 40 gigatonnes per year, the world has

about eight years left. To my mind, this simple fact is such a powerful

illustration of the challenge: the famous race to net zero needs a fast

start if we are to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

Were the world to

give up on the 1.5°C target and set the limit to 1.7°C or 2°C, the

remaining carbon budgets would amount to 550 and 900 gigatonnes,

respectively. This would allow a bit more time to get to net zero, as

illustrated in Figure 1, but it does little to reduce the urgency to act

and the environmental costs of any further delays.

Figure 1

Source: Author[s] calculations based on Table SPM.2 . IPCC Climate Change 21, The Physical Science Base,

If we were to

translate the remaining budgets into minutes until midnight, the clock

would say that it is 7 minutes to midnight for 1.5°C, 11 minutes to

midnight for 1.7°C, and 16 minutes to a midnight of 2°C warming. It is

worth noting that although the relationship between emissions and

warming seems to be near linear, the consequences of higher temperatures

are not. Another way of looking at these numbers is to conclude that we

need to develop carbon extraction technologies very fast and at

scale. Unfortunately, this technology does not seem to be ‘just around

the corner’.

Is the economics profession rising to the challenge?

Given the size of

the challenge, what are economists doing? Not much, according to Andrew

Oswald and Nicolas Stern (Chapter 1). They look at the number of papers

on climate change published in top economics journals and conclude that

the economics profession has been failing the world. According to

their count, the Quarterly Journal of Economics (QJE), for

instance, had not published even one article on the economics of climate

change until 2019 (a quick Google search for climate and QJE suggests

that this may be unchanged, although it does reveal one QJE article

published in 1917 on climate change as an element in the fall of Rome)....

more at VoxEU

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article