We analyse the effectiveness of policy tools for large-scale banking distress and draw lessons for today. The depth of recessions following banking distress depends both on the speed with which tools were deployed and their type and on the macro-financial vulnerabilities.

While, in general, swifter and broader-ranging policy actions

mitigate such recessions, central banks' asset purchases and lending are

particularly effective when banks have been underperforming or when

distress follows abnormally large asset price movements, such as those

triggered by the Covid19 crisis. Our analysis confirms that the recently

employed policies have supported the real economy.1

Banking distress and crises tend to be followed by deep recessions.

The basic reason is the sharp contraction in lending following a

breakdown in financial intermediation. Baron et al (2020) document that

after episodes of large bank stock price declines and an abnormal number

of bank failures - that is, after distress episodes - real GDP falls by

5.5% on average from peak to trough. Output losses are particularly

large when distress morphs into a full-scale banking crisis (Laeven and

Valencia (2013)). And they vary across countries. For example, during

the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) output fell from peak to trough by

0.16% in Switzerland and by almost 30% in Greece.

There are two interrelated sets of explanations for such variations

across countries and episodes. One relates to the initial economic

conditions, notably the macro-financial imbalances with which countries

enter a period of distress. For instance, banking distress associated

with the unravelling of a domestic financial imbalance (eg a housing

bubble) may have a very different impact than that stemming from an

external event in the absence of such or similar imbalances (eg a crisis

imported through cross-border exposures).2

The other set of explanations relates to the policies employed. The

timing and degree of policy activity and the specific tools deployed (eg

central bank lending, separation of impaired assets) differ

considerably across episodes. These choices will influence the severity

of the recession, not least if the effectiveness of tools varies with

the initial conditions.

Key takeaways

- Policy interventions that address banking distress also help support GDP growth.

- Central banks' asset purchases and

lending have generally been effective in supporting growth when distress

follows banks' poor performance, high private sector leverage or large

asset price corrections.

- Central banks' swift response to the

Covid-19 crisis has helped to support the economy, including by

pre-emptively staving off banking distress.

While many studies document the economic consequences of banking

distress, relatively few systematic cross-country analyses explore the

effectiveness of mitigating policy tools.3

Progress has been hamstrung by a lack of comprehensive data about these

tools. Furthermore, it is inherently difficult to measure

effectiveness. For example, larger-scale distress calls for stronger

interventions, but also makes success less certain. This may lead to the

spurious conclusion that interventions are less effective.

With this special feature, we make progress along three dimensions.

First, we classify 62 banking distress episodes into five categories, on

the basis of initial macro-financial vulnerabilities.4

Second, using a new database by Adler and Boissay (2020) on the

deployment of various distress mitigation tools, we assess empirically

whether variations in the evolution of GDP across similar episodes can

be explained by differences in the speed and type of policy

interventions. Third, we draw policy lessons for today from our

analysis.

We find that swifter and broader-ranging policy actions mitigate the

impact of banking distress on economic activity. We refine this result

in several ways. Central bank lending schemes are more effective in

helping restore GDP growth when set up in the first year of distress,

whereas impaired asset segregation schemes are more successful when used

in the second. Asset purchase and - to a lesser degree - liability

guarantee schemes are effective regardless of when they are deployed.

Our analysis of past experiences also suggests that certain tools are

particularly effective under specific initial conditions. For example,

we find that central bank lending schemes are most helpful when distress

follows unusually large asset price corrections of the type triggered

by the Covid-19 crisis. Our results confirm that the policy measures

adopted since March 2020 have helped to support the economy, including

by pre-emptively staving off banking distress.

The rest of this feature is structured as follows. The first section

describes how we classify banking distress episodes and, in the process,

documents their variety. The second describes the various policy

interventions, and includes a box on their variation by time of use and

across countries. The third section formally tests the effectiveness of

various policy interventions depending on their speed and the type of

episode. The fourth section applies these findings to the ongoing

Covid-19 crisis. A final section concludes.

Classifying banking distress episodes

Banking distress has various causes and can start from different

initial conditions. Such differences must be accounted for when

evaluating the effectiveness of policy interventions. Our approach

consists of classifying past distress episodes into categories, based on

the macro-financial vulnerabilities that preceded them.

We consider 62 past banking distress episodes from Baron et al (2020) for 29 countries over the period 1980-2016.5

Baron et al define a distress episode as one in which bank equity

prices fall by 30% year on year and there is a higher than normal number

of bank failures. Their list differs from others' (eg Laeven and

Valencia (2012, 2018)) in two ways. First, it features more episodes,

including many distress episodes that did not end in crisis.6 Second, the starting dates of the episodes are identified precisely by crashes in bank stock prices.

In order to classify banking distress episodes, we track the

evolution of a large set of macro-financial variables in the run-up to

these episodes. There are vulnerabilities when (some of) these variables

take on abnormal values (Box A).

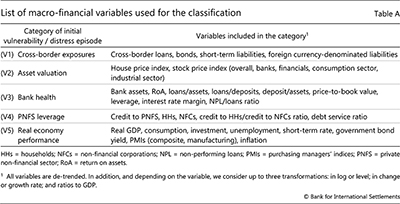

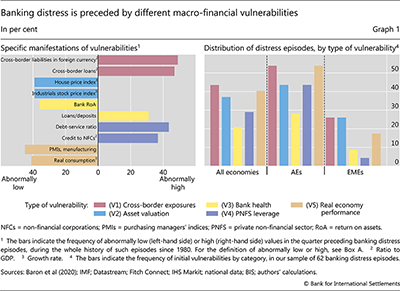

We classify the episodes into five categories, corresponding to five

broad vulnerability types: (V1) cross-border exposures; (V2) asset

valuations; (V3) bank health; (V4) private non-financial sector (PNFS)

leverage; and (V5) real economy performance (Graph 1, Box A

and Adler and Boissay (2020)). Vulnerabilities of the first type, for

example, typically stem from domestic residents' cross-border

liabilities in foreign currencies and cross-border bank loans (Graph 1,

left-hand panel). Those related to asset valuations show up as sharp

drops in house and stock prices (eg following the bust of an asset price

bubble). Vulnerabilities related to real economy performance manifest

themselves most often through a prior severe recession, with pronounced

falls in manufacturing PMIs and consumption growth.

Our classification highlights the variety of banking distress episodes. The right-hand panel of Graph 1

shows that in about 40% of the episodes, distress is preceded by

excessive cross-border exposure, severe asset price corrections7 or weak real economy performance. Weak bank performance only precedes 20% of the episodes.8

Box A

Definition of vulnerabilities and classification of distress episodes

This box describes how we identify the macro-financial

vulnerabilities that manifest themselves in the run-up to banking

distress episodes. We say that there is a (country-specific)

vulnerability whenever a variable takes on an "abnormally" high or low

value, ie when it falls in the upper or lower 10% tail of its

distribution. Since the immediate lead-up and aftermath of the episode

may distort the statistics, we follow Goldstein et al (2000) and

consider the distribution only for "normal times", defined as the period

that excludes the two years before and after the beginning of distress

episodes. We then investigate which variables took on abnormal values in

the distress episode's starting quarter (ie of the banks' stock price

crash), as well as the first, third and fifth quarters before that.

We consider a comprehensive quarterly data set of more than 70

macro-financial variables (in levels, growth rates, ratios to GDP) that

the literature has identified as potential early warning indicators of

banking distress (Table A). We group these variables into five categories relating to different

types of macro-financial vulnerabilities. This classification follows

common practice and is consistent with central banks' financial

stability monitoring frameworks.

We group these variables into five categories relating to different

types of macro-financial vulnerabilities. This classification follows

common practice and is consistent with central banks' financial

stability monitoring frameworks. Altogether, taking into account the number of variables and quarters

considered, the total number of potential vulnerabilities per category

ranges from 48 to 72, depending on the category.

Altogether, taking into account the number of variables and quarters

considered, the total number of potential vulnerabilities per category

ranges from 48 to 72, depending on the category.

To classify a distress episode, we first calculate the percentage of "abnormal" variables within a category. Then we classify an episode into a specific category if this percentage

is above a threshold of 25%. The classification is not mutually

exclusive: a given distress episode may be classified in multiple

categories. At the same time, the 25% threshold implies that three

quarters of the episodes are classified in at least one category and one

quarter of all episodes are classified as not preceded by any

vulnerability.

Then we classify an episode into a specific category if this percentage

is above a threshold of 25%. The classification is not mutually

exclusive: a given distress episode may be classified in multiple

categories. At the same time, the 25% threshold implies that three

quarters of the episodes are classified in at least one category and one

quarter of all episodes are classified as not preceded by any

vulnerability.

The data indicate some differences between advanced and emerging

market economies (EMEs). In advanced economies (AEs), distress episodes

tend to be preceded by widespread vulnerabilities, with notably

excessive cross-border exposure and weak economic performance (55% of

cases). In about 40% of the AE episodes, the initial conditions involve

severe asset price corrections or high private sector leverage. In EMEs,

it is harder to relate distress episodes to specific vulnerabilities.

Just one in four episodes is preceded by excess cross-border exposure or

a severe fall in asset prices, and few episodes by excess leverage,

whether in the financial or non-financial sector. This suggests that

banking distress in EMEs need not be the outcome of domestic imbalances,

but could be triggered by external shocks.....9

more at BIS

© BIS - Bank for International Settlements

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article